End of pipe solutions are in fashion. It's smarter to treat than avoid waste, to consume in order to save, to take a pill for stress, to arm teachers! At least, that's what we are told daily.

The sustainable use of pesticides directive (SUD) challenges end of pipe! It challenges the need for solutions to problems that might not exist if we hadn't created them. The solution it proposes is to avoid the problems. How extraordinarily revolutionary, or, in simpler terms, what remarkable common sense!

Legislation with straightforward requirements should be relatively simple to apply although "it's not necessarily so" as the blues song reminds us. The SUD doesn't altogether fit into this category. True, it contains straightforward elements such as care of sprays and sprayers, the protection of watercourses and the requirement to follow the instructions for use. All are easy to translate into dos and dont's although the PAN and European Commission implementation reports make clear much remains undone.

The SUD goes much further by setting out a vision and indeed obliging Member States to follow it with respect to integrated pest management (IPM). No need here to emphasise the significant lack of progress for, again, PAN and the Commission have already done so and Member States, by their silence, have confirmed the diagnosis. If you don't understand the vision, you don't understand the directive. Sadly, understanding is at a very low level.

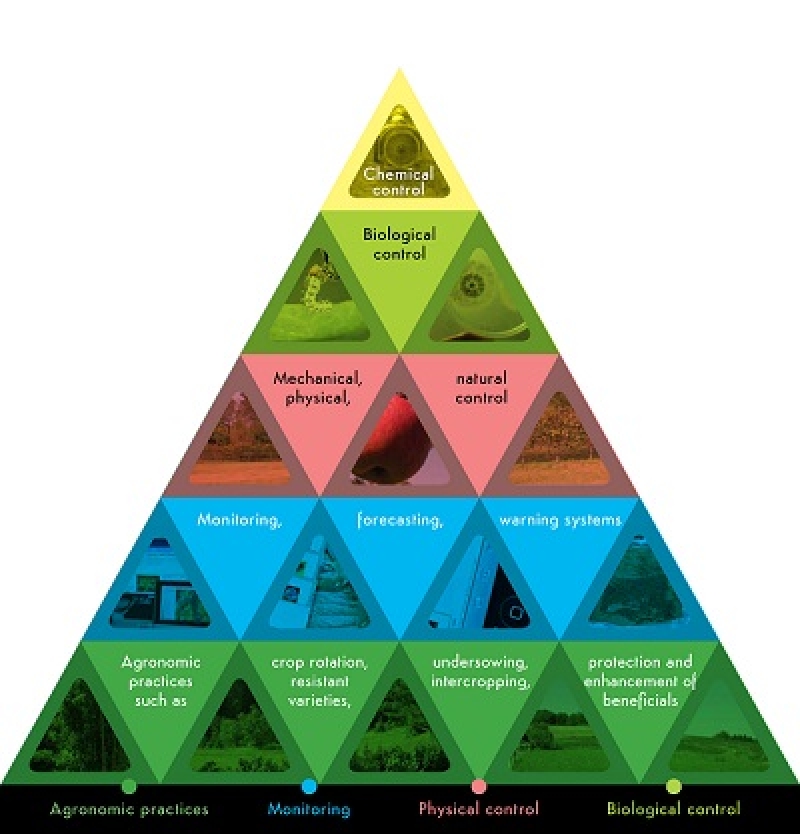

The heart of IPM is attention to cultural practices; make sure that the building blocks for them are in place and working and only when necessary have recourse to further protective measures such as biological control of pests and eventually chemical pesticides. The famous IPM triangle could not be clearer.

This is the essential background and the constant focus of the 6th symposia organised to date by PAN, IOBC-WRPS and IBMA, hosted by Pavel Poc MEP at the European Parliament in Brussels and continuously well attended by all relevant parties.

The early symposia addressed our state of knowledge on aspects from rotations to early warning systems and especially the thorny and ultimately frustrating business of authorisation for biological and low impact controls. The need for substitutes for chemical pesticides is important for farmers in their choice of crop. Providing such confidence should be a baseline objective but it seems absent. Yet, time and again at the symposia, individual farmers have reiterated they had moved to IPM and cited reasons such as profitability, retention of soil organic matter and structure, water management, biodiversity and their own health and safety as reasons for their move. Many indicated they had reduced pesticide use by more than half!

An early symposium examined the situation for the greenhouse sector, which many pesticides producers see as the natural home of IPM. This is understandable in the sense that the environment is more controlled but IPM is far broader than protected crops. Consumers were important drivers of change in the greenhouse sector, forcing supermarkets to demand changes in PPP use. Their reasoning was as much to protect workers and water as to ensure the lowest possible residue levels in the tomatoes, peppers and courgettes they purchase. That reasoning is valid across all agricultural sectors.

We then examined the apple and grape sectors to see how they fare. Great progress is reported not just in orchard and vineyard design but also in the provision of machinery more suited to lower PPP use. As importantly, Luxembourg is supporting its wine producers to move to IPM and providing the building blocks for farmers to build confidence and eventually capture quality market share through IPM. In Italy, where enormous strides towards IPM have been made through joint work of farmers, their cooperatives and researchers, there is great interest in using the CAP's crop insurance programme but the Commission itself needs further convincing.

The taboo subject of IPM has long been arable farming which accounts for about 50% of farmland use in the EU. Yet, at the 2018 symposium, farmers from France and Italy were abundantly clear that they see IPM as the profitable, intelligent, low cost, higher profit route in arable and provided figures to back up their argument. That is not to suggest that research, development and authorisation of biological and low risk control is not urgently required but to reinforce the point made by farmers that, already, the rotations, mechanical control and early warning systems have a major role in achieving IPM. Monoculture, with its built in problems for soil, water retention and pest build up is a farming concept not much older than 50 years. It has not proven itself sustainable despite its use of the props of inorganic fertilisers and PPPs to address every new problem. We may need also to look at grassland. Continuous grassland monoculture and animal slurry use presents its own weed problems with recourse to herbicides an increasingly common practice.

Progress on SUD implementation has been slow, so what's the value of the annual symposium? To me, as chairman since 2013, it has played an immense role in bringing together the various strands of the industry to debate out their viewpoints in front of European parliamentarians, Member states and Commission officials in the European Parliament. Great credit is due to the organisers who frequently have very different views. The speakers have brought to public and policy makers attention many important scientific findings relating to PPP use, most recently with respect to earthworms, soil bacteria and fungi none of which are good news.

The poor quality of implementation and the 3 year delay in the Commission report highlighted to the European Parliament whose own report will be published later this year, were certainly significant as clear messages of discontent from citizens. Certain other themes constantly come up;

- The need for a more ambitious vision so that common sense requirements within the SUD are routinely applied and that IPM becomes the norm with its success measured not least in substantially reduced PPP use across Europe.

- The urgent need to fully address the authorisation issue for biological and low risk control. The SME driving this should not be put out of business when it is their innovation which will bring the benefits of reducing much PPP use.

- The building blocks to help IPM need to be more fully emplaced and embedded into the CAP and this includes insurance where appropriate. But it also means that research, education, training, monitoring, early warning systems and independent advice are the norm rather than the exception.

- Finally, IPM needs to be seen as a business opportunity by large PPP companies. They need to forward plan with IPM in mind.

The SUD is a visionary directive. From the viewpoint of biodiversity and water protection its implementation is every bit as important as the EU biodiversity strategy and the water framework directive. Rachel Carson would be proud of its ambition! Without implementation, the stubbornly high use of PPPs will continue and the recovery of biodiversity and water quality be impossible. The directive does not advocate the exclusion of PPPs but sets a clear road whereby they are products of last rather than first resort, a reason in itself to continue with the symposia with the clear aim of farming via the IPM triangle. Measuring success will always be problematic, but, in my view, if a halving of current PPP use is achieved in the next decade including ongoing and increasing replacement by the better of the worse, then it will be an investment of incalculable value and, lets recall that France, a country heavily pesticide dependent today, is planning to go much further! So let's not be constrained in our ambition.

By Michael Hamell, Chairman of the Annual IPM Symposium