On the 60th anniversary of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, the book that helped trigger the modern environmental movement, pesticide contamination is higher than ever. This is also due to a failure of EU pesticide policies. A new PAN Europe report reveals a 100% failure rate of an EU law to ban the most harmful pesticides because officials follow rules created by industry.

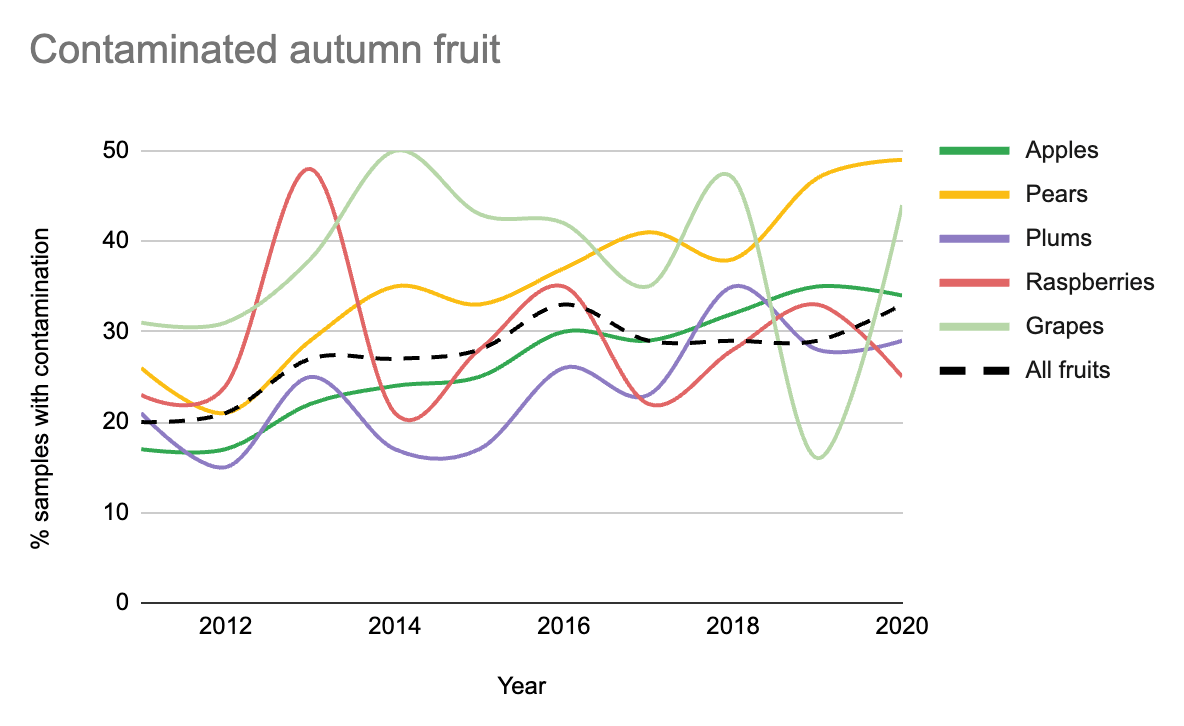

Autumn fruit is highly contaminated with the most hazardous category of pesticides, the latest government data shows. High rates of European pears (49%), table grapes (44%), apples (34%), plums (29%) and raspberries (25%) were sold with residues of pesticides linked to increased risk of cancer, birth deformities, heart disease and other serious conditions and/or toxic to the environment, the latest data shows [1]. Most are a threat even at very low doses. The problem has been getting worse. PAN Europe analysed 44,137 fresh fruit samples tested by governments from 2011 to 2020 and found that contamination of apples, pears and plums has nearly doubled since 2011.

Government sampling shows a dramatic rise in the rate of contaminated apples, pears and plums, with a steady overall rise for the dozens of fruits tested by officials.

Silent Spring and growing pesticide dependence

The report, titled Pesticide Paradise, how industry and officials protected the most toxic pesticides from a policy push for sustainable farming, comes 60 years to the day after publication of Silent Spring, the book that first alerted the public to the dangers of pesticides and helped spark the modern environmental movement. A central warning in the book was of a ‘pesticide treadmill’, where farmers use ever more chemicals to kill ever tougher pests. That cycle drives up industry profits, but is flawed, researchers say.

Since the book’s publication on 27 September 1962, pesticide use has gone up, species extinction helped by pesticides is occurring 1,000 times faster than normal, and illnesses linked to pesticides are estimated to cost Europeans up to 32 billion annually.

Corporate capture and regulatory failure

Recognising the problems, the EU agreed two important laws in 2009. The first to phase-out the most toxic category of pesticides where non-chemical alternatives are available, the second to push all farmers towards these safer techniques [2].

Today’s PAN report reveals that the pesticide phase-out has failed because governments are following guidelines written in close partnership with chemical giants BASF, DuPont (now Corteva) and Syngenta [3]. The document has not been covered in the mainstream media, despite its influence [4]. Unusually, and breaking EU regulatory independence values, the guidelines were adopted by the EU and copy-pasted into national guidance [5]. They are responsible for non-chemical techniques being rejected and the most toxic pesticides authorised on every occasion since the 2009 law, spanning hundreds of cases [6]. The guidelines achieve the opposite of what the law intended, actually promoting pesticides sold by the companies that helped write them [7]. The law to promote alternatives has largely failed.

Professor of Plant-Insect Interactions Félix Wäckers commented that: "There are a range of effective non-chemical solutions available that can be used as part of IPM. When considering the alternatives to a particular pesticide, this should not be restricted to alternative chemical classes only, but should also include these non-chemical alternatives.

The European Commission knew of the phase-out failure since at least 2018, but took no meaningful action. The guidelines should be replaced with ones that acknowledge the effectiveness of non-chemical alternatives to pesticides, PAN said. A new EU pesticide reduction target is doomed otherwise, it said.

PAN Policy and Campaign Officer, Salomé Roynel said: “Fruit is getting steadily more contaminated because industry is writing the rules and officials are ignoring non-chemical solutions. They are scratching each other’s back while the environment and our health suffers. Rachel Carson warned about this toxic relationship 60 years ago and would be tearing her hair out if she were alive today.”

European Parliament member Éric Andrieu (S&D), Anja Hazekamp (Left), Frédérique Ries (Renew Europe) and Thomas Waitz (Greens/EFA), leading voices on pesticide problems, regretted: “The fact the pesticide industry can completely switch the law we created from a restriction into an advantage is as shocking as it is embarrassing. 4 years after a large majority of the EP supported the recommendations of the Special Committee on the authorisation procedure of Pesticides (PEST), we cannot let this stand. As former members of PEST, we are going to hold the Commission and Member States to account, starting today. Those crooked guidelines have to be completely rewritten in order to foster sustainability.”

Over a third of Europeans are concerned about pesticide food contamination, according to official polling, with the issue the top concern in six European countries. In 2017, the second most popular EU certified petition was lodged, calling for a complete ban of pesticides. A Toxic 12 campaign calls on decision-makers to eliminate the worst pesticides urgently.

Contacts

- Salomé Roynel - salome [at] pan-europe.info (EN, FR), PAN Europe campaigner, + 33 7 68 39 72 74

- Jack Hunter - jack [at] fthe.fr (EN), PAN Europe communications consultant, +33 754 54 35 48

- Felix Wäcker - felix.wackers [at] solutionsbynature.eu (EN, DE), Professor of Plant Insect Interactions at Lancaster University

Notes

[1] Member state officials annually test European grown fruit on sale in stores for all forms of pesticides. Large sample sizes mean that officials consider the results representative of all fruit sold / general population exposure. PAN focused on results for a special category of pesticides that use 53 chemicals known as Candidates for Substitution (CfS), identified by EU officials as being highly toxic to humans, animals and/or the environment (see Annex II, point 4). Each is suspected of causing one or more severe impacts, such as cancer, birth deformities or heart disease. Most impact the endocrine system, so have no safe level. Pesticide cocktails can multiple their dangers, but are not investigated. From 2011, governments have been required by law to substitute them with safer alternatives.

[2] Non-chemical alternatives, defined in Annex 3 of Directive 128/2009, were supposed to become the main techniques used by all farmers. Governments were supposed (articles 14.1 and 14.4) to define, no later than 2014, how and when alternatives should be used, with chemicals a last resort. They all failed to do this, prompting the Commission to complain (letters to France, Croatia, Romania, Portugal).

[3] The guidelines were written by EPPO through a series of meetings by its working group on pest resistance. Industry fills a quarter of the working group’s membership, including two from Syngenta and two from DuPont. Industry at times organised meetings, and at times, outnumbered officials by two to one. NGOs were never invited. PAN complained, but nothing changed.

[4] EPPO was responding to Regulation 1107/2009, specifically articles 24, 50 and Annex 4, which force officials to reject applications for new CfS pesticides if effective non-chemical alternatives are available. But the guidelines strongly steer officials to approve CfS pesticides by stating at step B5 on page 4 that farmers should never be left without multiple types of pesticide (Modes of Action) to fight resistant pests. Modes are an industry concept and the EPPO guidelines match industry’s position exactly. Research shows modes are a false requirement in most cases because non-chemical alternatives can unlock large cuts in pesticide use, by up to 95%. Member states fail to properly consider these alternatives and always reject them.

[5] The Commission should have rejected the EPPO guidance on the grounds that it clashes with the 2009 laws and fails transparency and independence norms that regulators are required to follow. Instead it adopted them as soft law in 2014. All member states follow the EPPO guidelines without deviation, except Bulgaria which had failed to follow the law at all, as of 2018. Some have copy-pasted from the EPPO guidelines, namely Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany (p17), Portugal and Spain. Industry celebrates that EPPO guidelines are the “basis for many national guidance documents” (page 19) resulting in no product losses for an example company (page 7).

[6] Most member states do not publish details of how the guidelines are used. But an internal Commission document states (page 34) that CfS pesticides were authorised on 278 occasions by January 2018. PAN believes the figure today is around 500. Most states say the process is not working. They say they are not aware of viable non-chemical alternatives, while PAN accuses officials of ignoring non-chemical alternatives.

[7] When pesticides are authorised, farmers are under less pressure to use alternatives, so use the pesticides, which raises pest resistance and drives ever greater use of chemicals. For instance, Syngenta markets several fungicides containing CfS widely contaminating European fruit.